What to Know Before Purchasing an Electric Vehicle: A Buying Guide

We’ve bought numerous electric vehicles over the years, tested many back to back and spent more hours charging in grocery store parking lots than we care to admit. That’s why we put together this buying guide to help you determine how to choose the best EV, and we are also sharing our Top Picks, which we think are the best EVs in their class.

If you’re reading this prior to Sept. 30, 2025, you need to make your purchase or lease ASAP because that’s when the $7,500 federal tax credit expires. Our advice below still applies regardless of your purchase date, however. Compared with a gas-powered car, you’ll have to consider how far you can travel before needing to recharge, as well as how to “refuel” an EV, including possible home improvements to support EV charging, how long it takes to charge and where to charge publicly. Not all EVs are created equal in their charging capabilities.

Related: More EV News and Testing

Electric cars can be expensive, too, as many come from luxury automakers, and those that don’t often command premium prices, though dealer or manufacturer incentives can help if the car and buyer qualify. The purpose of this buying guide is to supply you with the information to help find the best EV for you.

For those who decide an EV is the right move, we took out the guesswork by driving and testing just about every new EV out there, and our team of experts agree these are the best:

- Top Pick 2-Row SUV: 2026 Hyundai Ioniq 5

- Top Pick 3-Row SUV: 2026 Kia EV9

- Top Pick Car: 2025 Hyundai Ioniq 6

- Top Pick Luxury: 2026 Lucid Air

- Top Pick Value: 2025 Chevrolet Equinox EV

- Top Pick Truck: 2026 Chevrolet Silverado EV

How Much Range Do You Need?

It’s not hard to get 300 miles of range nowadays, but how much range you need depends on how far you drive and whether you have Level 2 home charging. You may not need as much range as you think if you can charge overnight, where you’re essentially “filling up” your car every night. However, you may need more range than you think if you live in a colder climate, don’t have home charging (which we don’t recommend) or frequently drive long distances.

- Consider how many miles you drive daily, the weather where you live, your driving style and your ability to charge an EV at home.

- There is no “magic number” for rated range.

- To prolong battery life, it’s best to charge the battery to 80%-90% and not dip below 10%, so total range can also be misleading.

Home and On-the-Road Charging Differences

We recommend EV buyers have reliable Level 2 charging at home where an EV can replenish its battery in eight to 12 hours. Charging on the road is best for longer trips or emergencies because charging times and availability can vary depending on a number of factors, though DC fast chargers can typically charge a battery from 10%-80% in about 30 minutes.

- Charging is affected by many factors, only some of which can be controlled.

- An EV cannot accept more charge than its rated charging rate; charging at a “faster” charging station may not be any faster, depending on the vehicle.

- Just plugging into a normal 120-volt home outlet may not be enough to effectively charge at home.

- Public DC fast charging is improving, especially with the increased adoption of the North American Charging Standard plug, but it can still be expensive and impact the long-term health of the battery.

How EVs Drive

Even relatively slow electric cars are quick and responsive thanks to how immediately an electric car delivers its maximum power. No surprise: They’re also very quiet to drive, though there are some peculiarities to be aware of.

- Most EVs are quicker than gas-powered vehicles with similar horsepower ratings.

- Regenerative braking, especially one-pedal driving, takes some getting used to.

- Many EVs offer all-wheel drive for an added cost but come standard with rear-wheel drive, which may be less than ideal in winter environments.

- Some EVs also offer front-wheel drive.

Electric Car Pricing

Electric car shoppers will have to be more mindful about pricing now that the federal tax credits are ending Sept. 30. While more affordable EVs are coming, most EVs have higher upfront costs than comparable gasoline-powered vehicles, though the reduced cost of gasoline and maintenance over the life of the vehicle can help even the cost.

- The least expensive EV is the 2026 Nissan Leaf.

- EVs typically have higher upfront costs than comparable gas-powered vehicles.

- Shoppers should be aware of the expiration of federal tax credits and explore available state and local incentives.

How Do You Buy an EV?

Buying an EV may be a slightly different process than you’re used to if the automaker doesn’t have dealerships like traditional automakers.

- Some EV manufacturers offer direct-to-consumer sales.

- You can purchase a Tesla, Rivian and Lucid online, taking delivery at a local showroom.

- For those that don’t offer online purchasing, the process is nearly identical to buying a gas-powered vehicle.

What About the Federal Tax Credit?

The federal tax credit has previously offered up to $7,500 off the purchase or lease of a new EV, but that tax credit is set to expire Sept. 30.

- The federal EV tax credit expires Sept. 30.

- The IRS says delivery can occur after Sept. 30, and the credit can still apply.

- You may still be able to apply state and/or local incentives after Sept. 30.

What’s Next for EVs?

On the horizon are more affordable EVs, though there are many unknowns regarding federal funding for more on-the-road DC fast chargers.

- New Nissan Leaf, Chevrolet Bolt and less expensive Rivians are coming soon.

- This is an inflection point for the EV market.

- More affordable EVs are coming, and even more would help offset the loss of federal incentives.

How Much Range Do You Need?

Key Takeaways:

- Consider how many miles you drive daily, the weather where you live, your driving style and your ability to charge an EV at home.

- There is no “magic number” for rated range.

- To prolong battery life, it’s best to charge the battery to 80%-90% and not dip below 10%, so total range can also be misleading.

It’s difficult to say just how much range you need. You might not need as much as you think, or you might need more range than you think. Ideally, your home becomes the “gas” station, so every night you plug in and recharge the car to start the day with range replenished. Recent data suggest the average driver travels approximately 40 miles per day, so with adequate home charging, you’d be in good shape with almost any EV without much variation in daily driving habits, especially as more and more EVs offer at least 300 miles of EPA-estimated total range.

The 2025 EV with the lowest EPA-rated driving range is the Fiat 500e with 141 miles (priced from $32,495, including destination), and the EV with the longest range is the Lucid Air Grand Touring with 512 miles of range (that version is currently priced at $116,400). Most EVs priced between $35,000 and $60,000 have between 200-300 miles of range, but models with more than 350 miles of range may cost significantly more.

There are several reasons you might need more range than you think. One is that automakers recommend you only charge the battery to 80% or 90% on a regular basis — and try not to drop below 10% if you can avoid it — to extend its life, saving a full 100% charge for long trips. That means you’re immediately cutting the EPA-estimated, manufacturer-advertised range by up to 30% for daily use if you want maximum longevity.

Being able to charge daily (without which you should reconsider EV ownership) also doesn’t account for worst-case scenarios like being away from home when range is falling fast. According to a 2025 study by Recurrent, modern EVs temporarily lose an average of 20% of their range when temperatures drop from “ideal” (68-74 degrees Fahrenheit) to 32 degrees. This is attributed to battery capacity loss at colder temperatures and the need for heating the cabin, which robs range. Modern EVs tend to have heat pumps, which are more efficient than resistance heaters in older EVs — so older EVs could be more adversely affected by colder weather. Based on an overall 40% decrease in range, an EV with a rated range of 250 miles could have only 150 miles of range when it’s 32 degrees outside, if only temporarily. In addition, some reports show EV batteries lose 5%-10% of overall capacity over the span of five years, so, worst-case scenario, that 250-mile range might get you only 125 miles in cold weather after five years of ownership. There’s a reason why EVs have been so popular in warm-weather states like California. Our experiences with our former long-term Tesla Model Y during subzero temperatures in January 2024 and later during a cold-weather range test provide some insight into how cold weather can affect the EV ownership experience.

How much range you need depends on how far you drive, in what conditions, and your access to public and home charging. It also depends on how you drive: EVs are less efficient at highway speeds and more efficient at lower speeds, and the EPA gives a glimpse with usage-specific mpg-equivalent ratings: The 2025 Hyundai Ioniq 6, in its long-range, rear-wheel-drive configuration with 18-inch wheels, is rated at 144 mpg-e in the city and 370 miles of range, 120 mpg-e on the highway and 308 miles of range, and 132 mpg-e combined with 342 miles of range.

If all conditions are favorable, you might not need as much range as you think, but if you have a deficiency in any of the above, it may make sense to pad your range with a higher-range model or version. Sometimes range diminishes on higher-cost versions because they often include all-wheel drive or performance upgrades with the same battery but higher-output motors, which use more power and lower overall range; because of that, sometimes the standard range is also the longest range, but it varies from car to car.

Home and On-the-Road Charging Differences

Key Takeaways:

- Charging is affected by many factors, only some of which can be controlled.

- An EV cannot accept more charge than its rated charging rate; charging at a “faster” charging station may not be any faster, depending on the vehicle.

- Just plugging into a normal 120-volt home outlet may not be enough to effectively charge at home.

- Public DC fast charging is improving, especially with the increased adoption of NACS, but it can still be expensive and impact the long-term health of the battery.

When shopping for a traditional gas car, you don’t have to consider how quickly the gasoline flows out of your local gas station’s pump or how quickly your car can accept gasoline. But with an electric car, comparable limitations do exist, and owning one that can replenish its battery quickly enough for your lifestyle is the difference between a good and bad EV experience. How much time it takes to charge an EV (and how many miles of range it represents) depends on a number of factors, including the battery size, the vehicle’s overall efficiency, its onboard charger, and the capacity of both the external charger (technically the EV service, or supply, equipment, which is what hangs on the wall and plugs into the car) and the electrical circuit that feeds it.

The three charging levels that loosely bracket how fast an EV can charge are Level 1, Level 2, and DC fast charging, which we detail in our explainer. Your home is filled with electrical outlets, but most are 120 volts; they’re just not practical to charge a modern long-range EV’s huge battery because they can only replenish its range at speeds of 3-5 miles of range per hour, meaning an empty EV with 250 miles of range would take 50 hours(!) in the best-case scenario. Granted, charging from empty to full is rare and (again) not recommended for battery-health best practices. Replenishing after shorter trips (say, 40 miles) could take between eight and 13 hours.

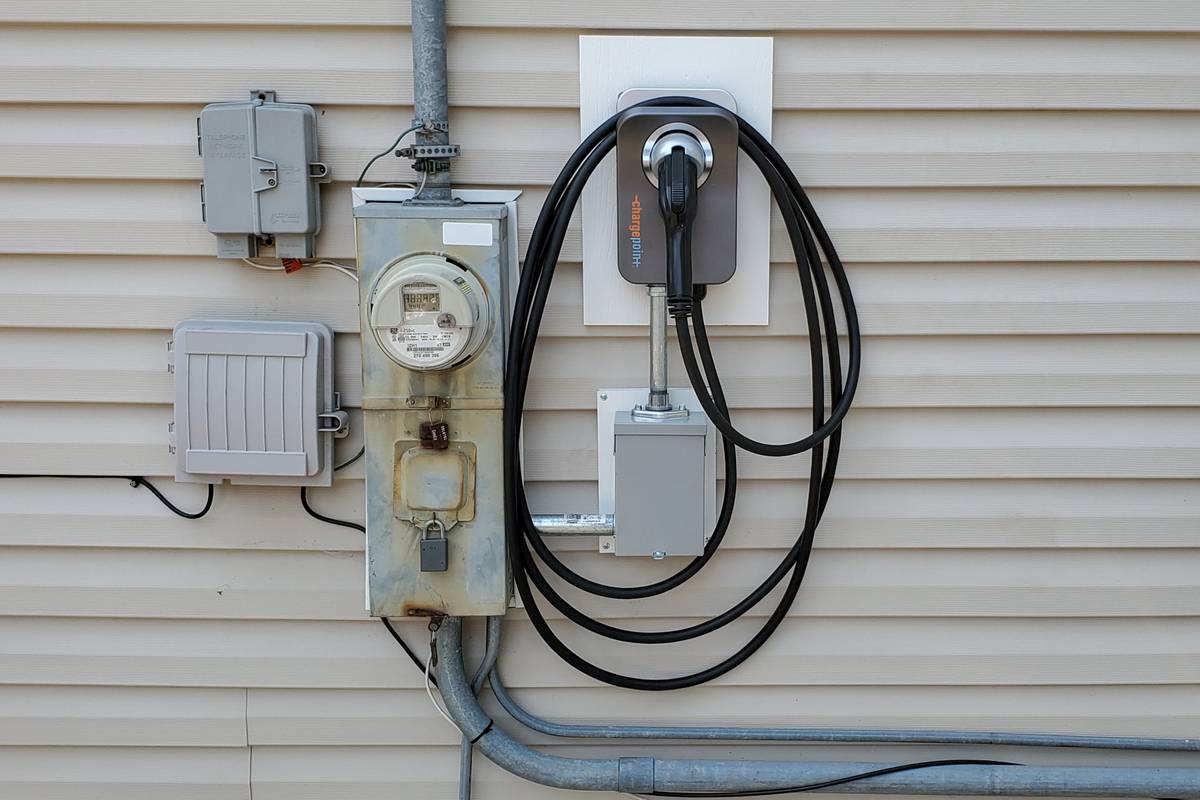

For modern EVs, we recommend 240-volt Level 2 home charging, which can add 5.5-60 miles of range per hour depending on the car, charger and home charging circuit. Charging power for Level 2 spans 3-19.2 kilowatts, which is the measure of charging-speed potential; Level 1 circuits commonly max at a scant 1.8 kW.

More power (in kilowatts) doesn’t always mean one EV will charge faster than another because of differences in the vehicles themselves. Some simply accept more power, as explained in the first of five things that could slow your EV’s home charging speeds.

Then there’s efficiency. Charge times can vary based on ambient temperature, battery temperature, charge percentage, grid usage, battery age and health, and more. You may be asking why we’re not mentioning battery size, measured in kilowatt-hours; that’s because it’s really not the end spec on which you should be focused. Battery size is equivalent to the gas tank size on a conventional car, which can’t be separated from the car’s efficiency; higher efficiency means more miles of range on the same battery. For charging times, a smaller battery on one EV could actually charge more slowly than a larger battery on another.

While most EVs include a charging cord that facilitates Level 1 charging, some include or sell a Level 2-capable “mobile charger” with the vehicle, including Tesla, Ford’s Mustang Mach-E and the Chevrolet Equinox EV. These standard apparatuses are a good starting point if there’s a lower-amperage 240-volt circuit from an appliance like an electric clothes dryer available, but they aren’t as fully featured as available hard-wired, wall-mounted units that cost hundreds of dollars and are often required for the faster charge time. Mobile chargers of this type are typically limited to 32 amperes, providing around 7-ish kW to the car.

The more expensive hard-wired installations (required for 48-80 amps) are worth the cost if you’re driving more miles per day because they can charge faster as long as the vehicle can support it. In 2022, we had six home chargers installed in the Chicago area at an average of around $3,800 per home on a mix of townhomes and houses, which you can read more about in our story detailing what it cost us to outfit six homes with EV chargers. A 2024 installation at another editor’s home in the Chicago area cost approximately $2,400, which brings our average cost down slightly to just over $3,600.

DC charging is the fastest way to charge but isn’t feasible for homes due to the cost and power levels required, so it’s available only at public or commercial charging stations. While enticing, DC charging is expensive when not included as a limited incentive with a new car purchase, and it’s not recommended for frequent use in order to preserve maximum battery life, so it’s best for longer trips where stations are commonly placed along popular highways or in emergencies. DC fast-charging speeds vary even greater than for Level 2, from 24-350 kW, though even at its most powerful isn’t close to as fast as you can pump gasoline into a traditional car.

Tesla Superchargers commonly span 72-kW, 150-kW and 250-kW speeds, with newer 325-kW “V4” chargers coming online, and every new Tesla can charge at each one. Tesla made its proprietary NACS plug available to all automakers, and numerous manufacturers have started selling EVs with a built-in NACS plug and access to the Supercharger network; in the meantime, existing EVs from those automakers are gradually gaining access and can use the network via an adapter. How owners acquire the adapter varies from automaker to automaker and even by time of purchase. DC fast-charging options are also available from networks like Electrify America and EV Go, which have chargers that span 24-350 kW. Not all cars can take advantage of the higher-power units, however, and the 350-kW chargers are mostly along popular highway corridors. EVs that can take advantage of the 350-kW chargers include the Audi RS E-Tron, GMC Hummer EV, Hyundai Ioniq 5 and Ioniq 6, Kia EV6 and EV9, Lucid Air, Porsche Taycan, and Rivian R1S and R1T, but not all EVs can match the charger’s potential. A Lucid Air is limited to 300 kW, a Kia EV6 and Hyundai Ioniq 5 max at 240 kW, Rivians are currently limited to “over” 200 kW but there are plans to offer 300-plus kW in the future, and the GMC Hummer EVs are claimed to charge at just under 350 kW (346 kW).

Fast-charging capability of 150 kW and greater is found on current EVs like the Ford Mustang Mach-E and Volkswagen ID.4. Earlier EVs, such as the first- and second-generation Nissan Leaf, first-generation Chevrolet Bolt EV, Hyundai Kona Electric and Kia Niro EV, rarely exceed 50-90 kW.

In our experience, the claims of being able to charge from “this percentage to that percentage in 16 minutes” are often not consistently repeatable because weather, battery or other conditions prevent maximum charge speeds. On the faster end in our testing have been Hyundai, Kia and Genesis EVs with 800-volt charging capability that in warmer weather replenished batteries from 18%-80% in as little as 18 minutes, which added 162 miles of predicted range on a Kia EV6 and 152 miles of range on a Hyundai Ioniq 5. Charging a Genesis Electrified G80 from 16%-80% took 20 minutes to add 187 miles of range.

How EVs Drive

Key Takeaways:

- Most EVs are quicker than gas-powered vehicles with similar horsepower ratings.

- Regenerative braking, especially one-pedal driving, takes some getting used to.

- Many EVs offer AWD for an added cost but come standard with RWD, which may be less than ideal in winter environments.

- Some EVs also offer FWD.

One of the most exciting experiences of driving an EV is being thrust into your seat after pressing the accelerator, which is experienced even in most lower-powered EVs. An electric motor makes its maximum torque at low speeds, so hitting the accelerator provides instant acceleration. There’s no traditional step-gear transmission, so there’s no waiting for downshifting or the engine’s speed to climb to get more power like a gasoline-powered car.

Unlike a traditional gas-powered car — which can only employ a single, more powerful engine to get more power — an EV can have two or more motors. Traditional AWD mechanically links the front and rear wheels with a driveshaft, but EVs accomplish the same with one or two motors at each axle. You’re essentially getting two engines when you choose an AWD EV, so that version will almost always be quicker than the two-wheel-drive version. And fast is right: Two of the five quickest cars we’ve ever tested have been EVs, with the 2021 Porsche Taycan Cross Turismo Turbo S’ 0-60 mph time the quickest ever at 2.9 seconds and the 2025 Hyundai Ioniq 5 N needing just 3.29 seconds to get there.

The downside is that range is often diminished with an extra motor (or a more powerful one) when used with the same battery.

The Toyota bZ, Ford Mustang Mach-E, Kia EV6, Hyundai Ioniq 5 and Subaru Solterra are just some of the mass-market EVs that offer AWD, and the number is growing. Expect to pay a premium for an AWD EV over a RWD or FWD model.

With an extra motor, additional regenerative braking can recuperate energy and soften the potential hit to range. Regenerative braking, which recycles energy that would otherwise be lost during deceleration, is a characteristic that will vary by EV and is a staple of all-electric driving. It’s often used to maximize efficiency through a one-pedal driving mode where the accelerator pedal is used to accelerate and brake — as you ease up on the accelerator, the car engages its regenerative braking to aggressively slow the car without requiring use of the brake pedal in normal driving. (You still have to use the brake pedal for heavier/emergency braking.)

Unique to EVs is the return of the RWD standard configuration. Many EVs have standard RWD with optional AWD (ID.4, Mustang Mach-E, Ioniq 5, EV6, etc.) versus the common FWD layout of most mass-market cars and light- to medium-duty SUVs. FWD cars tend to behave more predictably in slippery conditions, though we only have limited experience with RWD EVs in wintry conditions. EVs are heavy because the large batteries by themselves can weigh a thousand pounds or more, so a compact electric SUV like the Ioniq 5 at its lightest 4,000-pound curb weight can weigh nearly the same as a three-row SUV like Hyundai’s Palisade, which is at minimum 4,171 pounds. Because of this extra weight, traction might prove better than in a traditional RWD gasoline-powered car.

Electric Car Pricing

EV prices span from under $30,000 to well over $100,000, and, as previously mentioned, are usually pricier than similar gas-powered vehicles. In September 2025, the average list price of all new EVs on Cars.com was $66,981, compared to the $49,912 overall new-car average.

How Do You Buy an EV?

Key Takeaways:

- Some EV manufacturers offer direct-to-consumer sales.

- You can purchase a Tesla, Rivian and Lucid online, taking delivery at a local showroom.

- For those that don’t offer online purchasing, the process is nearly identical to buying a gas-powered vehicle.

Innovation and EVs go hand in hand, and that extends to the buying process, as well. Non-legacy automakers like Tesla, Rivian, Lucid and Polestar all offer direct purchasing processes where interested buyers order their desired model and features, usually pay some sort of reservation fee or deposit, wait for their car to be built and then complete the purchase. When we bought our Tesla Model Y, Cars.com’s Editor-in-Chief Jenni Newman ordered the car and said, “Purchasing the Model Y couldn’t have been easier. It was frankly easier than ordering groceries online.” For consumers who need to finance, these newer companies often offer their own financing, as well.

For the majority of EVs, however, buyers will simply need to follow the traditional purchase process just like any gas-powered car. Consider the factors we’ve already mentioned about range and home charging, then add them to the advice in our other buying guide and you’ll be taking home your EV in no time.

What About the Federal Tax Credit?

Key Takeaways:

- The federal EV tax credit expires Sept. 30, 2025.

- The IRS says delivery can occur after Sept. 30, and the credit can still apply.

- You may still be able to apply state and/or local incentives after Sept. 30.

The federal tax credit expires Sept. 30. Automakers and dealers are offering deals to shoppers in advance of the expiration date — for both leases and purchases. And, according to the IRS, you don’t necessarily have to take delivery of your new EV on or before Sept. 30 to receive the credit. You can learn about the lease or finance deals, the “loophole” for applying the credit after its expiration, and you can also see what to expect. You can find the IRS’ list of still-eligible vehicles here.

If you’re buying an EV after Sept. 30: You’re out of luck, at least from the federal government. State and local incentives may still apply, depending on where you live and purchase your EV. You may want to consider a less expensive variant of the EV you’re interested in, or an altogether different and more affordable model.

What’s Next for EVs?

Key Takeaways:

- A new Nissan Leaf, Chevrolet Bolt and less expensive Rivians are coming soon.

- This is an inflection point for the EV market.

- More affordable EVs are coming, and even more would help offset the loss of federal incentives.

The good news for shoppers interested in EVs is that the depth and breadth of all-electric offerings continues to expand even as automakers revise or scale back future electrification plans. There also appears to be a greater push to making EVs affordable before any incentives are applied. The redesigned 2026 Nissan Leaf and coming second-generation Chevrolet Bolt EV will fill the bottom of the pricing spectrum, along with the upstart Slate Truck. Rivian is also introducing a number of smaller, more affordable SUVs.

The bad news for EV shoppers is that the end of the federal EV tax credit, along with uncertainty surrounding topics like tariffs and federal EV infrastructure funding are likely to impact affordability, availability and usability, though how much remains to be seen.

With more choices than ever before (and more on the way), EV shoppers have a lot to look forward to even if the road ahead isn’t perfectly smooth.

Cars.com’s Editorial department is your source for automotive news and reviews. In line with Cars.com’s long-standing ethics policy, editors and reviewers don’t accept gifts or free trips from automakers. The Editorial department is independent of Cars.com’s advertising, sales and sponsored content departments.

Featured stories

Should Tesla Model Y Owners Get the New 2026?

2026 Nissan Leaf Review: Value Victory